When Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia moved to San Francisco in late 2007, they weren’t looking to disrupt the global hospitality industry. They were simply two designers living in a loft they couldn’t afford, facing a looming rent payment and an empty bank account.

At the time, San Francisco was overflowing with conference attendees, and every hotel in the city was booked solid. In a moment of classic entrepreneurial improvisation, they bought three air mattresses, set them up in their living room, and offered a place to sleep plus breakfast to stranded travelers. They called the experiment “Air Bed and Breakfast.”

From Literal Airbeds to Laboratory Lessons

The initial name was entirely literal, but the experience served as a live laboratory for a new kind of product. Chesky and Gebbia quickly realized that hospitality isn’t defined by a lobby or a concierge; it is built on trust, clear photography, and human connection.

The early listings in 2008 were raw think couches and spare rooms, but they offered something hotels couldn’t: a slice of local life. This realization shifted their perspective from a survival trick to a hypothesis. They began to believe that travelers might actually prefer a stranger’s home over an anonymous hotel room if the experience felt authentic and safe.

Building the Infrastructure of Trust

Turning a quirky idea into a functional platform required technical muscle. Nathan Blecharczyk joined as the third co-founder and Chief Technology Officer in early 2008, bringing the coding expertise needed to launch airbedandbreakfast.com that August.

Despite the launch, the early days were painfully slow. Traction was minimal, and the founders faced the grueling reality of a startup with high energy but zero cash flow. Many companies would have folded here, but the Airbnb team took a famous detour into the world of breakfast cereal.

To fund their runway, they created and sold novelty Obama O’s and Cap’n McCain’s cereal boxes during the 2008 presidential conventions. This scrappy marketing stunt didn’t just pay the bills; it caught the eye of Paul Graham at Y Combinator. Though they had missed the initial application deadline, their sheer persistence earned them a spot in the January 2009 batch, providing the mentorship and credibility they desperately needed.

Scaling the Human Element

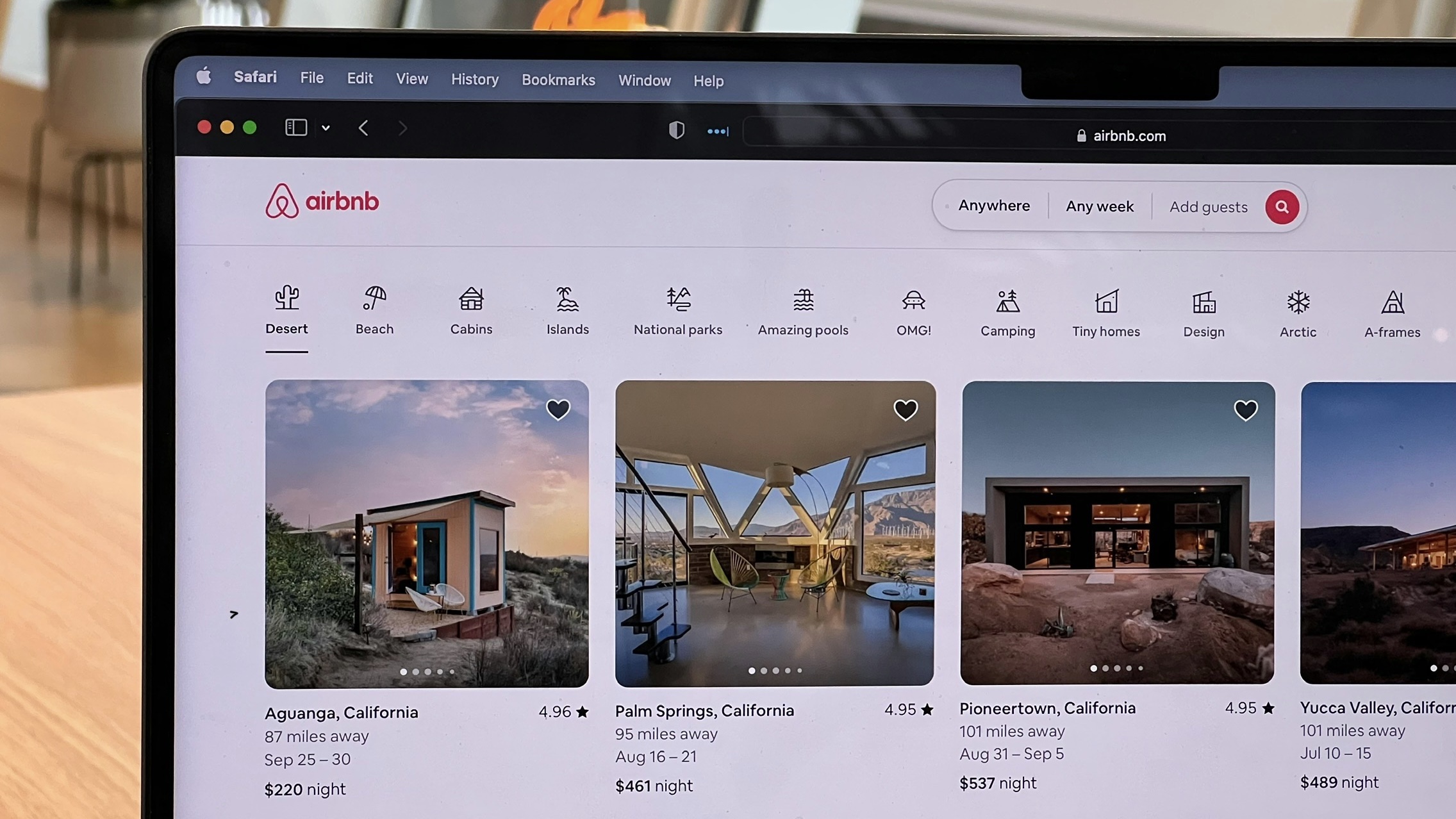

Under the guidance of Y Combinator, the team moved away from the air mattress experiment and reframed Airbnb as a sophisticated marketplace for short-term lodging. They obsessed over the details that professionalized the platform, such as professional photography for listings, host guarantees, and verification systems.

This transition was critical. By standardizing cancellation policies and trust systems, they converted a messy, local act of hospitality into a repeatable global product. They moved from a niche for adventurous backpackers to a mainstream option for families and business travelers alike.

The DNA of a Disruptor

The true story of Airbnb is far spikier than the polished founding myth often told at tech conferences. It was a journey of technical fixes, marketing stunts, and a thousand small decisions regarding user trust.

The company’s DNA remains rooted in that original rent day hack. It serves as a reminder that big disruptions rarely start with a perfect market analysis. Instead, they begin with a specific problem and a willingness to try something small and human. For modern innovators, the lesson is clear: focus on practical solutions to immediate problems. Whether you are using a platform like Magnetech to scale an idea or building from your own living room, the key is to test, listen, and let the market guide your growth.

Leave a Reply